Quark Watch (July - December 2002)

December 21, 2002

The impulse to post con reports comes and goes. Lately, it hasn't nagged me very strongly, but I feel that I should at least share such tidbits of fannish political news as I've picked up at places like Midwest Construction, Windycon, Loscon and SMOFCon.

Worldcon, 2006: Underdog Kansas City has quickened the pace of its campaign. It threw bid parties at both Windycon and Loscon, then made quite an impressive showing at SMOF Diego. There bids were given the opportunity to present "infomercials" between program items, and, of the ones that I heard, only KC's caught the spirit of the idea. Bid chairman Margene Bahm also announced that she has secured promises of low hotel room rates, which can't hurt. On the down side for the Kansans, their campaign was lifeless for two years and hasn't much time to make up lost ground. Rival Los Angeles can boast a large, experienced, well known fan organization while the KC talent pool is distinctly thin and untested outside its local area. A factor with unpredictable impact is dates: L.A. will hold the convention a week before the standard Labor Day weekend. Some fen will abhor any alteration of custom; others will applaud the reduced conflict with children's back-to-school schedules.

Worldcon, 2006: Underdog Kansas City has quickened the pace of its campaign. It threw bid parties at both Windycon and Loscon, then made quite an impressive showing at SMOF Diego. There bids were given the opportunity to present "infomercials" between program items, and, of the ones that I heard, only KC's caught the spirit of the idea. Bid chairman Margene Bahm also announced that she has secured promises of low hotel room rates, which can't hurt. On the down side for the Kansans, their campaign was lifeless for two years and hasn't much time to make up lost ground. Rival Los Angeles can boast a large, experienced, well known fan organization while the KC talent pool is distinctly thin and untested outside its local area. A factor with unpredictable impact is dates: L.A. will hold the convention a week before the standard Labor Day weekend. Some fen will abhor any alteration of custom; others will applaud the reduced conflict with children's back-to-school schedules.

Worldcon, 2007: The Nippon in 2007 bid, for Yokohama, Japan, was greeted with much enthusiasm when it surfaced a couple of years ago. I am now starting to hear worries about whether a Japanese-run Worldcon will bear more than a passing resemblance to the traditional event. Because of linguistic and cultural barriers, almost no Japanese fans work on Worldcons, and the fairly small number who attend don't mingle a lot with the rest of the congoers. Hence, they might not be able to put on Worldcon-as-we-know-it, however much they want to. That may not be a very good reason to vote against them, but it's one that could influence a substantial number of voters. High air fares and hotel costs are also unhelpful. These factors give the competing Columbus bid, which has started running bid parties but still has only the outline of a bid committee, such faint hope as it has. Its proposed venue is the Columbus Convention Center, site of Marcon and the Origins annual wargaming convention. Back when Columbus was a fannish superpower, it never managed to win a Worldcon or NASFiC, and I wouldn't bet heavily on its doing better now.

Worldcon, 2007: The Nippon in 2007 bid, for Yokohama, Japan, was greeted with much enthusiasm when it surfaced a couple of years ago. I am now starting to hear worries about whether a Japanese-run Worldcon will bear more than a passing resemblance to the traditional event. Because of linguistic and cultural barriers, almost no Japanese fans work on Worldcons, and the fairly small number who attend don't mingle a lot with the rest of the congoers. Hence, they might not be able to put on Worldcon-as-we-know-it, however much they want to. That may not be a very good reason to vote against them, but it's one that could influence a substantial number of voters. High air fares and hotel costs are also unhelpful. These factors give the competing Columbus bid, which has started running bid parties but still has only the outline of a bid committee, such faint hope as it has. Its proposed venue is the Columbus Convention Center, site of Marcon and the Origins annual wargaming convention. Back when Columbus was a fannish superpower, it never managed to win a Worldcon or NASFiC, and I wouldn't bet heavily on its doing better now.

Worldcon, 2008: Er, will there be a 2008 World Science Fiction Convention? When the switch to the current no-zone system was being debated, proponents of change stressed that the elimination of rotation among zones would expand the number of cities eligible to bid each year and thus reduce the danger of a year with no bidders. The WSFS business meeting bought that argument -- and now, for the first time in modern Worldcon history, we are within two years of a Worldcon vote and have no site in prospect. Under the old arrangement, 2008 would have been a Western Zone year, for which Los Angeles would undoubtedly have launched a bid (assuming that 2005 still went to Britain). As it is, L.A. is running for 2006. The best hope at this point is that the loser of the 2006 race will turn around quickly and announce for '08, though both bids have, not surprisingly, pooh-poohed that idea.

Worldcon, 2008: Er, will there be a 2008 World Science Fiction Convention? When the switch to the current no-zone system was being debated, proponents of change stressed that the elimination of rotation among zones would expand the number of cities eligible to bid each year and thus reduce the danger of a year with no bidders. The WSFS business meeting bought that argument -- and now, for the first time in modern Worldcon history, we are within two years of a Worldcon vote and have no site in prospect. Under the old arrangement, 2008 would have been a Western Zone year, for which Los Angeles would undoubtedly have launched a bid (assuming that 2005 still went to Britain). As it is, L.A. is running for 2006. The best hope at this point is that the loser of the 2006 race will turn around quickly and announce for '08, though both bids have, not surprisingly, pooh-poohed that idea.

Worldcon, 2009: After initially favoring 2010, the folks behind the nascent Chicago bid have decided that 2009 is a better idea than a contested race against the Australia in '10. An official launch is likely at Torcon. One potential complication is that, if Kansas City manages to win the 2006 race, Chicago will not be eligible in '09, because the no-zone scheme rules out sites within 500 miles of the Worldcon at which the vote takes place. Chicago fen who figure that out may turn into a pro-L.A. voting block.

Worldcon, 2009: After initially favoring 2010, the folks behind the nascent Chicago bid have decided that 2009 is a better idea than a contested race against the Australia in '10. An official launch is likely at Torcon. One potential complication is that, if Kansas City manages to win the 2006 race, Chicago will not be eligible in '09, because the no-zone scheme rules out sites within 500 miles of the Worldcon at which the vote takes place. Chicago fen who figure that out may turn into a pro-L.A. voting block.

Worldcon, 2010: My ConJosé report has the tale of the inception of the Australia in '10 bid. Stephen Boucher, the conscripted bidcomm chairman, announced at SMOFCon that the Aussies will decide within a few months whether they really want to run. If they do, there will be a big party at Torcon. If they don't, there will be an even bigger party, to get rid of the funds that have been thrust into Stephen's hands. The venue will almost certainly be Melbourne, following in the footsteps of previous Aussiecons. Sydney remains too expensive, Perth is too far away from everything, and there are no other cities on the continent with adequate facilities for even an Aussie-sized Worldcon.

Worldcon, 2010: My ConJosé report has the tale of the inception of the Australia in '10 bid. Stephen Boucher, the conscripted bidcomm chairman, announced at SMOFCon that the Aussies will decide within a few months whether they really want to run. If they do, there will be a big party at Torcon. If they don't, there will be an even bigger party, to get rid of the funds that have been thrust into Stephen's hands. The venue will almost certainly be Melbourne, following in the footsteps of previous Aussiecons. Sydney remains too expensive, Perth is too far away from everything, and there are no other cities on the continent with adequate facilities for even an Aussie-sized Worldcon.

NASFiC, 2005: With the Worldcon overseas in 2005, there will be a NAFiC vote at Torcon. The competitors are Seattle and Charlotte. Very strangely, Charlotte all but bypassed Windycon -- no party and an out-of-the-way table manned only sporadically. Seattle had both a party and a bid table. The contrast was particularly odd when one considers that the chairman of the Charlotte bid is from Chicago. The Charlotte crew made a respectable effort at Loscon, but that is a far less important convention when the balloting will be held 2,000 miles away.

NASFiC, 2005: With the Worldcon overseas in 2005, there will be a NAFiC vote at Torcon. The competitors are Seattle and Charlotte. Very strangely, Charlotte all but bypassed Windycon -- no party and an out-of-the-way table manned only sporadically. Seattle had both a party and a bid table. The contrast was particularly odd when one considers that the chairman of the Charlotte bid is from Chicago. The Charlotte crew made a respectable effort at Loscon, but that is a far less important convention when the balloting will be held 2,000 miles away.Letter of Comment: Irv Koch (3/31/03)

September 23, 2002

Why begin

Till we know that we can win?

And if we cannot win,

Why bother to begin?

So sing the caricatured "cool, conservative men" in 1776, but two and quarter centuries have wrought changes. The era when being "progressive" had anything to do with looking forward has passed, as the Left has grown unadventurous and reactionary. As a final step in the process, the self-proclaimed "aggressive progressive" Web site Democrats.com has now come out in favor of absolute stasis as the best policy, at least in the realm of science.

The news last week that the U.S. government had approved a private enterprise lunar venture was greeted with nothing but alarm at Democrats.com. Three consecutive posts denounced the scheme. First, the site's readers were warned that the whole thing was a plot by the military-industrial complex:

U.S. Military Control of Space from the Moon: The Real Plan behind TransOrbital's Permission to 'Develop' the Moon?

Everyone by now knows with painful clarity that the Bush administration does not do a single thing without having something in it for them, and usually something big and juicy. Now put two and two together: Bush gives a wacko commercial company with a scheme called the Artemis Project the green light to be the first to commandeer the moon, commercially - that means patents and legal privilege of a sweeping and unprecedented nature. Now add to that the USS Space Command's long range plan - military control of space. It doesn't take more than two neurons to figure out that once the Artemis Project gets its foot in the lunar door, the "state-sponsored" construction of a military space base will follow.

Next came deeper probing into the underlying conspiracy:

TransOrbital Just Like Bush - Long on Grandiosity and Corporate Schemes, Short on Real Science

The company that Bush turned the moon over to as its personal corporate playground is a chip off the old Blockhead. Check out this home page: http://www.transorbital.net/index.html - notice the ad at the top of the page, where the company brags that it will make it possible to display commercial messages on the surface of the moon. Now check this site out for the Artemis Society - the group that is behind TransOrbital. It reminds us of those rghtwing [sic] front sites that lead to multiple front sites and nothing is what it seems. You'll notice that their web host calls itself the "Illuminati" and is based in Texas. How Bush/Rumsfeld/Cheney can you get!? Here's another one of their "subsites": Project Leto, a moon tourism outfit based in Las Vegas to attract the glitzy crowd.

Yes, yes, I know that it reads like a parody: If your ISP hails from Texas, you're part of the Vast Right-Wing Conspiracy. But - I affirm this at the risk of being disbelieved by all sensible folk - Democrats.com is not a parody Web site. [N.B.: I've added the links to the preceding quotation; the progressives apparently haven't yet mastered that high-tech accomplishment.]

Finally comes the "scientific" objection, raised not just against TransOrbital's proposals but against all human contact with Luna:

While Nation Looks the Other Way on 9/11 Anniversary, Bush Gives Moon to Private Corporation for 'Industrial Development'

Like all the other international laws, Bush is now ignoring those pertaining to space. As America is distracted by 9/11 remembrances and warnings of new threats, His Heinous has turned the moon over to a private, for-profit corporation called TransOrbital that has a far-reaching, frigthening [sic] agenda for the corporate domination of space. All TransOrbital had to do was promise not to contaminate and pollute the moon - yeah, right. That's what the oil companies say about ANWR. There was no Congressional vote - not even any consultation. Bush simply acted as if the moon were his to give away. The TransOrbital venture could be disastrous for the globe - no scientist today could predict yet how adding mass to the moon via human infrastructure or removing mass, via mining, will impact the delicate gravitational interplay between Earth and its only satellite. The moon belongs to all the people of the Earth - not to George. W. Bush or his friends at TransOrbital. [emphasis added]

Yup, tamper with the Moon and the sky will fall on our heads.

Such silliness was too much for at least one progressive, who e-mailed a loc demolishing the last post's notions about "delicate gravitational interplay":

Whether or not Bush or TransOrbital plans to own the moon is besides the point. If they do plan to own it, then we shall stand against it.

However, we should NOT just assume for no apparent reason that they are doing this. I, being a space enthusiast, have been following the efforts of TransOrbital and several other new space exploration companies, and see no reason to suspect anything.

Stooping to conspiracy theories is a very low thing to do. As leftists, it undermines our integrity. It undermines our claim to morality. Instead of "attacking" the company, perhaps you should find our more about it.

Worst of all, is your claim that we can destabilize the Moon's orbit. If this is the case, then space exploration would be impossible. But that is not the case. Both the Earth and the Moon are bombarded with hundreds of tons of space dust each day. On top of that, the solar wind exerts an extremely large amount of force on both the Moon and Earth. The moon is normally hit with very large objects, as its surface shows. It's delicate balance would've already been disturbed billions of years ago. What you stated is very scientifically inaccurate. As a society, we really undervalue science. Most people are very scientifically ignorant. We do not need more ignorance. One fourth of American adults do not know that the Earth revolves around the sun. That is a sad state of affairs. We do NOT need anymore ignorance and anti-intellectualism than we have today. Instead, we need to PROMOTE scientific knowledge and excellence.

I know that you have your own opinions. If you cannot shake your suspicions of TransOrbital, then I don't have THAT much of a problem with that. But please, for the sake of our future, do not post false scientific facts. If there is something you do not know, please consult an actual scientist. Don't help with the spread of ignorance.

In reply, the site's scientific genius, Cheryl Seal by name, offers a screed about how "the most disturbing type of scientific ignorance out there is that displayed by many scientists", that is, by all of those who undermine Miz Seal's opinions. On the dangers to the Moon's orbit, she takes the "precautionary principle" to new heights:

If you are conversant with the current scientific/mathematical fields of interest, then you should be familiar with chaos theory. The slightest - and we're talking SLIGHTEST variation introduced into a system can, over time, become magnified many times over.

Our progressive expert sees both "short-term" and "long-term" risks here. In the short run,

To add mass to the moon in the abrupt and nondistributed way that human development would add it could, especially to a system into which such variables have never been introduced, produce subtle effects felt on Earth. For example, it could intensify tides by a tiny, tiny fraction - but under certain conditions, that could be enough to trigger more intensive earthquake activity on earth. It would also trigger more substantial tides and contribute to devastating storm surges - not the best deal when water levels are rising steadily in coastal areas already.

The long run is yet more frightful:

In the long-term, even if there are no immediate obvious effects from a slightly altered gravitational interplay between Earth and moon, the chaotic effect could, ultimately produce catastrophic changes (greatly enhanced tides, disastrous climate effects, etc.). Are we so selfish and short-sighted that we don't care what happens to people several centuries or millennia from now - or have we just written the possibility of a human future on Earth completely off? Easier to desert the sinking ship and head for new worlds to exploit, eh?

Now, if one must be so fearful of the "SLIGHTEST variation", what safe course of action is there except to do nothing whatsoever? How, indeed, does Miz Seal defend her own introduction of variation into "the system"? Who can imagine what dire effects may flow from the subtle air currents set in motion by her fingers as they strike the keys on her computer? Not to mention the heat the her computer generates - and the electrons that flow unnaturally to carry her thought-substitutes to the world! Cheryl Seal, you are putting the whole ecosystem, perhaps the universe itself, in peril! Just sit there quietly. Don't type. Don't breathe. Try not to think. Well, that last one is easy.

September 13, 2002

ConJosé, the 60th World Science Fiction Convention, faced greater challenges than most. In the science fiction community, now strongly dependent on computer skills for income, the recession was deeper, more traumatic and slower to end than in the rest of the country, and the Worldcon’s attendance pickup was correspondingly laggard. The last Progress Report before the convention carried dire warnings that familiar amenities would have to be dropped unless lots of members appeared at the last minute.

Meanwhile, the concomm for a long while gave the impression that it was having too much fun fighting among itself to pay much heed to the necessities of running a convention. Dire whispers spread that ConJosé would be a repeat of Nolacon - minus the French Quarter.

Many fans like to anticipate disaster, but I’m afraid that hopes of a decade’s worth of horror stories (the ones about Nolacon are getting longish in the tooth) were disappointed. ConJosé wasn’t a breakthrough in con running, but it suffered no more than the usual quota of blunders. By the last day of the con, scarcely a discouraging word was audible anywhere.

For the record, let it be noted that there were blunders: A number of badges weren’t printed. The Green Room opened without hot water for tea. The fan exhibits area started out in chaos, no one having ever been appointed to run it. The Art Show ran short of panels. The list of past Worldcons in the Program Book contained strange errors (misspelling the names of three of the six Chicon 2000 Guests of Honor, for instance). The party lists in the daily newszine were incomplete. A microphone died at the Hugo Awards Ceremony. Registration couldn’t (or at least didn’t) furnish daily membership list updates to the Worldcon site selection voting staff. Handicapped Access could have used more motor scooters, though the concomm can’t be blamed for failing to foresee the damage that the convention center’s unyielding concrete floors would inflict on fandom’s aging knees and feet.

What’s noteworthy about this litany of mistakes is how petty they were. What we did not observe were constant program changes, late starting events, bungled room layouts, misdirecting signage and other indicia of loss of control. In fact, a fan who didn’t happen to step into one of the minor puddles wouldn’t have noticed that it was raining at all.

Some of the problems had the consolation of producing amusing stories. It took Registration two days to find Tony Lewis’ badge - not because it didn’t exist but because it read “Anthony Lewis”, and no one thought to look for it under that name. Tony was reminded of an incident that occurred when he was working registration at Torcon 2 in 1973. He couldn’t find the badge belonging to a woman who came to his station and asked her to go to the problem desk for help. She insisted that she had bought a membership and demanded her badge. Tony assured her that the problem desk would take care of the matter. She repeated herself in a louder voice and didn’t budge. After a couple of more rounds, Tony said, “Ah, I see what’s wrong. Your name begins with the letter ‘V’, and there is no ‘V’ in the Canadian alphabet.” “Oh,” said she, “I didn’t know that” and proceeded docilely to the problem desk as directed. The kicker was that her home address was in Victoria, British Columbia.

My own badge had the accurate but unexpected label, “Edward Thomas Veal”. That gave me several opportunities to say that the badge maker, when he came across a guy named “Veal” from Chicago, clearly had no idea who that might be, which shows that, no matter what one does in fandom, it will be forgotten. I find that notion comforting.

Turning now to things that were done right, the convention facilities, while not an esthetic marvel, were a good size and configuration for a Worldcon. The main hotel was just a trifle farther from the convention center than one would have liked, but a 500-yard walk through central San Jose on a warm, sunny weekend is no burden - a marked contrast with the last Bay Area Worldcon, San Francisco in 1993, where many of us had to trudge half a mile through grimy downtown areas to reach a convention center that was enormously out of scale to the convention. The San Jose center had three exhibit halls of the right dimensions for the Art Show, Dealers’ Room and Exhibits area and a sufficient number of program rooms. An auditorium across the street hosted the Masquerade, the Hugo Awards ceremony and a surprise Friday night appearance by Patrick Stewart.

I didn’t see enough of the program to feel qualified to comment on its overall quality, but it looked good in the Pocket Program. As at Chicon 2000, program items were 75 minutes long with 15 minutes’ passing time, a schedule that I am more and more convinced ought to become standard at Worldcons. Panels have a less constrained feel, and getting between them is far less hectic, than when 55 minute events are squeezed into 60 minute slots.

My only role as a program participant was to moderate a panel on the burning question of whether the lead time for Worldcon site selection should be reduced from three to two years. It was billed as a debate, but the three scheduled panelists - Andrew Adams, Mark Olson and Ben Yalow - were all on the “two year” side, so I had to draft an audience member to provide opposition. Though the issue has twice been the subject of close WSFS business meeting votes in recent years, emotions did not run high, and I doubt that any audience member left with the fervent conviction that the business meeting needs to vote on the matter a third time in the near future.

The most intriguing-sounding panel that I didn’t see was called “Peake vs. Tolkien” and was supposed to consider what fantasy might look like if run-of-the-goblin writers took their inspiration from Gorghemghast rather than The Lord of the Rings. China Miéville has begun to give us, in Perdido Street Station and The Scar a glimpse of “alternate fantasy”, but his work is distinctly on the grim side. One can imagine a Peake-derived tradition in other veins, too.

I didn’t see the Masquerade at all but assume, from the fact that it disgorged its crowds by ten o’clock, that it either had fewer entrants than usual - not necessarily a bad thing - or was run with brisk efficiency - definitely a good thing.

The Hugo Awards ceremony was slightly too long and didn’t sparkle, but it also didn’t commit any horrible faux pas. The lone technical glitch came at the beginning, when Toastmaster Tad Williams’ microphone wouldn’t work. There was another mike on stage, so the event was delayed for only a minute or two. Unfortunately, the technical delay paled beside the self-imposed slow pacing of the “front matter” preceding the awards themselves. I’m not one of those who gripes about handing out other honors before the Hugos, but I do gripe about allowing them longer time slots than the main events. The First Fandom, Big Heart, Seiun and Cordwainer Smith Awards occupied nearly 40 minutes, the 14 Hugo Awards a little over 60. The upshot was that almost all of the Hugo presenters were limited to "The nominees are. . . . and the winner is. . . ." What's the point of having well-known fans and pros do the presenting if they say nothing more than that?

An innovation was a speech by the Toastmaster, delivered after the preliminary awards and before the presentation of the Hugos themselves. Williams’ talk was well-written and well-delivered, but the ceremony is already crowded. I suspect that this practice will not become a tradition.

The Awards themselves held three big surprises. First, Neil Gaiman’s American Gods took the honors for Best Novel, overcoming not only the electorate’s traditional aversion to fantasy but competition from well-regarded books by perennial winners Connie Willis and Lois McMaster Bujold. Second, Ellen Datlow, of the Webzine Scifi.com, broke Gardner Dozois’ string of Best Editor Hugos. Third, while the Best Dramatic Presentation Hugo was not at all a surprise, everybody was astonished when two of the stars of The Fellowship of the Ring, Sean Astin (Sam Gamgee) and Sala Baker (Sauron), came forward to accept it. Two years ago, the producers of GalaxyQuest showed up at the ceremony, so maybe Hollywood is beginning to pay a modicum of attention to fandom. If so, my hypothesis is that the development is an offshoot of studios’ interest in using the Web as a publicity vehicle. To create “buzz” on the Web, it’s essential to pay attention to active buzzers, of which fandom doubtless has more than its fair share.

Next year a new Hugo will join the crowd. An amendment to the WSFS Constitution, splitting Dramatic Presentation into “long” (more than 90 minutes) and “short” forms, won final passage by a surprisingly large three-to-one majority (96-26, with yours truly in the beleaguered minority). A glance at this year’s nomination statistics shows why the new award is likely to prove feeble. Only four “short forms” (i. e., television series episodes) received as many as nine nominations (the cutoff for reporting by the Hugo administrators). Two of those were Buffy the Vampire Slayer episodes that drew respectable support, enough in one case to make the final ballot, but two nominees do not a viable category make. Predictably, nominations will be widely scattered, and places on the final ballot will require so few votes that luck will be more determinative than quality. It will also be difficult for voters who are not TV addicts to see the nominees. Accessibility used to be a serious problem for the short fiction categories. The willingness of publishers to post nominees on the Web has made reading them less of a chore, but it will be a long time, if ever, before we have similar sources of television programs.

No Worldcon would be complete without fannish politics, which centers, naturally, around Worldcon bids. The 2005 race lacked suspense: Unopposed Glasgow defeated a scattering of frivolous write-ins and will host “Interaction” on August 4-8, 2005. Next year’s Worldcon will vote on the location of the 2005 NASFiC. (For those who may not know, the NASFiC is a North American convention held only in years when the Worldcon is outside the Western Hemisphere.) Candidates Charlotte and Seattle had bid tables and parties at ConJosé, and picking a favorite isn’t easy. Charlotte has been campaigning longer, having segued straight into NASFiC competition from its unsuccessful 2004 Worldcon bid. It seems to have plenty of money (its bid parties were lavishly provisioned, though unimaginative) and is led by former Worldcon chairman Kathleen Meyer (Chicon V in 1991). Its weaknesses are the perception that Charlotte is short of local fandom and its east coast location, which may make it more a competitor with than a complement to the Worldcon.

Seattle, by contrast, has a large, active fan base, well seasoned by annual Norwescons and frequent Westercons, but its contact with national fandom is weak. What fans outside the area think they know about local fandom is that its 1997 Westercon killed the Seattle in 2002 Worldcon bid. (It wasn’t a bad Westercon, but the hotel manager didn’t like it, and his grumbling made it impossible for the Worldcon bid committee to obtain options on facilities.) If the Seattlites campaign vigorously at cons outside their immediate vicinity, they have a good chance of victory. If they remain isolated in the Pacific Northwest, the race won’t be close.

The 2006 contest had been looking like a one-horse event. Los Angeles pushed its “Space Cadet” gimmick everywhere, while Kansas City, except for a few advertisements, remained invisible. At ConJosé the KC-ers threw off their slumber, though their table and parties were noticeably less crowded than L.A.’s (no big surprise in California, of course). I would rate L.A. a clear favorite, but the fact that the voting will be in Toronto could lead to an upset.

A swarm of eager Japanese fans showed up to promote “Nippon in 2007”. Their newly announced competition is Columbus, a city that has tried several times but never won a Worldcon race. The new Columbus bid was very low-key, and its prospects seem minimal. The organizers’ real goal, I suspect, is to get the inside track on what would likely be (owing to the high cost of going to Japan) a bigger-than-average NASFiC.

So far, no bids have appeared for years after 2007. This is about the time when, in the old, pre-no-zone cycle, candidates for 2008 would be started to emerge, but there hasn’t been a whisper. The Kansas City bid has declared firmed that it is interested only in 2006 (as the 30th anniversary of the last and only K.C. Worldcon), and the group contemplating a new Chicago bid has focused, for hard-to-divine reasons, on 2010.

Likewise blank is 2009, but the year after that already has the beginnings of a race. As noted, there is Chicago interest in 2010, and ConJosé witnessed the birth, under odd circumstances, to be sure, of a potential Melbourne in ‘10 bid.

According to what is probably reliable rumor, Aussie fan Stephen Boucher was lolling at a party in the wee hours of Sunday morning when Mark Olson teased him with the suggestion that Australia bid for the NASFiC if Japan won the 2007 Worldcon. (No, Australia isn’t really eligible to host a NASFiC; it’s a convoluted SMOF joke.) Stephen grumbled about how, if he was going to do the work of bidding, he’d rather have a Worldcon.

Fatal words. It took only a couple of minutes for others in the room (conspicuously not including Stephen, but his consent was regarded as a mere technicality) to decide on “Let’s Do It Again - Melbourne in ‘10” as a slogan, from which they inferred that 2010 would be the bid’s choice of year. Erik Olson (no relation to Mark) began selling presupports for 20 of whatever currency you have available. By the end of the convention, over 175 had been sold, plus several “Friend of the Bid” presupports at 100 whatevers apiece. Artist Sue Mason executed a t-shirt design on the spot. By morning, shirts were on sale at Scott and Jane Dennis’ booth. I’m told that they moved about 90.

The convention drew to a close with silly, but well-executed closing ceremonies. Torcon 3 chairman Peter Jarvis, arrayed in smoking jacket and gigantic top hat, accepted the gavel from ConJosé's co-chairmen Tom Whitmore and Kevin Standlee, and off we go to another year of fannish frolic.

September 2, 2002

Here are the Hugo Award results for the fiction categories. Shown in brackets is the number of nominations that each work received.

Best Novel

Winner: American Gods by Neil Gaiman [121 nominations]

Other nominees: Passage by Connie Willis [78]; The Curse of Chalion by Lois McMaster Bujold [71]; Perdido Street Station by China Miéville [64]; Cosmonaut Keep by Ken MacLeod [44]; The Chronoliths byh Robert Charles Wilson [44]

Other works that received significant numbers of nominations: Declare by Tim Powers [33] (not actually eligible this year and sadly overlooked last year); Revelation Space by Alastair Reynolds [33]; Nekropolis by Maureen F. McHugh [27]; The Outpost by Mike Resnick [26]; The Skies of Pern by Anne McCaffrey [24]; Thief of Time by Terry Pratchett [24]; The Other Wind by Ursula K. LeGuin [22]; Spherical Harmonic by Catherine Asaro [20]; Deepsix by Jack McDevitt [20]; Point of Dreams by Melissa Scott & Lisa A. Barnett [20]

Best Novella

Winner: "Fast Times at Fairmont High" by Vernor Vinge [40]

Other nominees: "The Chief Designer" by Andy Duncan [55]; "Stealing Alabama" by Allen Steele [51]; "May Be Some Time" by Brenda Clough [50]; "The Diamond Pit" by Jack Dann [41]

Other works that received significant numbers of nominations: "The Finder" by Ursula K. LeGuin [36]; "The Caravan from Troon" by Kage Baker [35]; The Last Hero by Terry Pratchett [35]; "Bug Out!" by Michael Burstein & Shane Tourtelotte [34]; "New Light on the Drake Equation" by Ian R. MacLeod [33]; "Yesterday's Tomorrows" by Kate Wilhelm [32]; "deck.halls@boughs/holly" by Connie Willis [31]; "Saturday Night Yams at Minnie and Earl's" by Adam Troy-Castro [28]; "View Point" by Gene Wolfe [21]; "Eternity and Afterward" by Lucius Shepherd [19]; "Shady Lady" by R. Garcia y Robertson [13]; "Great Wall of Mars" by Alastair Reynolds [13]

Best Novelette

Winner: "Hell Is the Absence of God" by Ted Chiang [33]

Other nominees: "Undone" by James Patrick Kelly [43]; "The Days Between" by Allen Steele [42]; "Lobsters" by Charles Stross [33]; "The Return of Spring" by Shane Tourtelotte [27]

Other works that received significant numbers of nominations: "Into Ironwood" by Jim Grimsley [24]; "The Measure of All Things" by Richard Chwedyk [23]; "Isabel of the Fall" by Ian R. MacLeod [23]; "Computer Virus" by Nancy Kress [19]; "Mirror" by Robert Reed [18]; "And No Such Things Grow Here" by Nancy Kress [16]; "Have Not Have" by Geoff Ryman [16]; "The Old Rugged Cross" by Terry Bisson [15]; "The Quijote Robot" by Robert Sheckly [15]; "Troubadour" by Charles Stross [15]

Best Short Story

Winner: "The Dog Said Bow-Wow" by Michael Swanwick [35]

Other nominees: "The Ghost Pit" by Stephen Baxter [30]; "Old MacDonald Had a Farm" by Mike Resnick [28]; "The Bones of the Earth" by Ursula K. LeGuin [26]; "Spaceships" by Michael Burstein [21]

Other works that received significant numbers of nominations: "Cut" by Megan Lindholm [20]; "In Glory Like Their Star" by Gene Wolfe [19]; "The Great Miracle" by Michael Burstein [18]; "Cold Calculations" by Michael Burstein [14]; "Senator Bilbo" by Andy Duncan [14]; "Incognita, Inc." by Harlan Ellison [14]; "Interview: On Any Given Day" by Maureen F. McHugh [13]; "Magpie" by Meredith Simmons [13]; "The Infodict" by James van Pelt [13]; "Whisper" by Ray Vukcevich [13]

ConJosé has posted the complete Hugo count for those who enjoy gobs of mostly meaningless data. I note that my prediction that The Lord of the Rings would receive two-thirds of the first place votes in Best Dramatic Presentation wasn't far off. It racked up 66.44 percent.

July 28, 2002

Rounding out my reviews of Hugo-nominated short fiction are the novelettes, where the entries are closely bunched.

1. To describe “Hell Is the Absence of God” (available as a free download from Fictionwise until the end of August) as Ted Chiang’s riff on the Book of Job risks turning away readers, who will anticipate pretentious blather on the order of Archibald MacLeish’s J.B. A better comparison would be Arthur C. Clarke’s classic story “The Star”.

In our world, God works in mysterious ways. Chiang hypothesizes one where Acts of God are visible and palpable. Every once in a while, an angel touches down on earth. These visitations twist the natural order in ways that are both welcome and otherwise. Some who see the angel descend are healed of incurable disease or regrow lost limbs or are filled with joy by a shaft of divine light. Others are afflicted with deformity or killed by the violence of the divine irruption into the material world.

Also visible are the destinations of departed souls. When Neil Fisk’s wife is fatally touched by an angel, she is seen ascending into heaven. Others go to hell, on which windows occasionally open, showing a realm not much different from mortal life except for the utter absence of God.

Neil Fisk’s misfortune is not as spectacular, but just as life-blighting, as Job’s. He loves his wife, longs to see her again in heaven and knows that reunion is impossible unless he loves God. But how can one love a deity who commits random murder? And if he loves God as a means of reunion with Sarah, what kind of “love” is that?

Neil’s search leads him to comforting answers that cannot stand up to scrutiny and across the paths of other seekers, whose blessings or curses from God lead to further questions. At the climax of the story, he accepts a final answer, but, like the words given to Job from the whirlwind, it is an answer that transcends the question.

I know nothing about Ted Chiang’s religious opinions, and “Hell Is the Absence of God” cannot easily be identified with any theological stance. Commendations like “challenging” and “thought provoking” have gone stale. Here is the sort of work for which they should be reserved.

2. “The Days Between” by Allen Steele (also available as a free download from Fictionwise until the end of August) is a sequel to Best Novella nominee “Stealing Alabama” but is a of a very different kind. Where its predecessor resembled a bad episode of Mission Impossible, this story recalls the best half hours of The Twilight Zone, even if it does suffer from a scientific gaffe so elementary that both author and editor should apologize contritely to the shade of Isaac Asimov. (Hints: How much acceleration is needed to maintain a constant velocity in a vacuum? How fast and how far would a starship go if it accelerated at one gee for 32 years?)

We begin three months after dissidents from an inept near-future dictatorship took over the starship Alabama, now bound for Tau Ceti on a 230-year voyage. The passengers and crew are all slumbering in cryogenic stasis. Then one is wakened by accident. He soon learns that going back into hibernation is impossible, as is communication with Earth. The ship has ample food and water. He can look forward to a normal lifespan, but he will live it utterly alone and in great danger of boredom. The ship’s library is well stocked with useful information but dreadfully short of entertainment, and playing chess against an unbeatable computer opponent has limited appeal.

Lt. Commander Leslie Gillis passes through frustration, despair and madness before he finds a purpose to his existence. How he finds it is testimony to the power of hope and to the role of imagination in making life worth living. Quiet and understated, this tale shows that defeats can be suffered and triumphs won in arenas far removed from political intrigue and war.

3. “Undone” by James Patrick Kelly (also available as a free download from Fictionwise until the end of August) begins in the midst of an interstellar war and ends in an idyllic sanctuary presided over by an accidental goddess who is finally able to set warfare aside.

Mada has been bred (or, more accurately, designed) as a warrior, whose reason for being to carry on the struggle against the anti-individualistic Utopians. That reason loses much of its immediacy when she is forced to flee 20 million years into the future, where/when she discovers that the war is over, mankind has vanished from the stars, and only a remnant population leads an eloi-like existence on a safe, protected Earth purged of all bad memories.

True to her training, Mada refuses to cease fighting merely because the enemy is gone. The last half of the story consists of her effort to breed a new revolutionary army and break back into the past, until she comes to realize that there are greater goals than victory.

The story displays a wide range of moods - excitement, mystery, humor myth - without fragmenting into incompatible shards. The ending has the dedicated revolutionary accept a bourgeois fate after surprisingly mild resistance, but the reason for her failure will charm any reader who has spent much time around pre-schoolers.

The qualitative gap between this story and the two that I have ranked above it is measured in microns. If any of this year's Hugo nominees have shots at being remembered as 21st Century classics, these three (along with Andy Duncan's novella "The Chief Designer") are the ones.

4. "The Return of Spring” [beware the misspelling in the URL] by Shane Tourtelotte is an earnest, well-meaning piece that calls attention to a looming social problem, but it is closer to an essay in fictional guise than a story.

In 2039 the aging of the baby boomers has made Alzheimer’s Disease into an epidemic scourge, to which the government has reacted with a massive, impersonal program of custodial care, one aspect of which, we learn as a casual aside, in official encouragement of “termination of treatment”, that is, the murder of the diseased by their caretakers.

What could be a greater boon at such a time than a treatment that restores Alzheimer’s victims to more or less full mental capacity? Joe Dipano is one of the first beneficiaries of the still-experimental cure. His family, unlike most, has looked after him at home, and he is enthusiastic about picking up life with them as a full member of the household instead of a painful burden.

But coming home again proves not to be so easy. The scars inflicted on those near to him by Joe’s long senility are slow to heal, and he meets with only grudging acceptance from children, grandchildren and neighbors. He also begins to fear that, elderly and bereft of savings and skills, he will remain a burden of a different kind.

The presentation of Joe’s disillusionment is moving but slightly schematic, and its resolution is artificial. It is unfortunate, too, that, for the sake of making a point, Joe’s family are such an self-centered, narrow-minded lot. Their lost father has been miraculously restored to them, and all that they can do is grumble about how hard things were while he was incapacitated. If he ends up fabulously rich, a possibility held out at the end of the story, I hope that he has the good sense to cut the ingrates out of his will.

5. “Lobsters” by Charlie Stross (also available as a free download from Fictionwise until the end of August) is a typically frantic day in the life of Manfred Macx, freelance altruist and crusader for the “agalmic economy” (one in which there are no scarce goods, so that the obsolete concept of economic exchange is superseded by gift-giving). Today’s highlights are Manfred’s matching of a disaffected Russian A.I. to a job suited to its talents and his reconciliation with his ideologically incompatible fiancée, a dominatrix whose day job is recruiting taxpayers for the IRS.

The cyberpunk goings-on are fast-paced though not always comprehensible, and the story is fun on a superficial level. The protagonist is, however, a self-contradictory personage. One side of his brain preaches that goods and services, particularly knowledge, should be freely given away. He prides himself on enriching others. Meanwhile, his other brain half is busily patenting inventions and devising ways to make those patents more far-reaching (to cover “not just a better mousetrap but the set of all possible better mousetraps”). It’s true that he donates all of those patents to a not-for-profit foundation with noble objectives, but that is not quite the same thing as putting ideas into the public domain. I’m not sure that the author notices the dissonance between theory and action, but perhaps I give him too little credit. A possible reading of the story is that Manfred and Pamela come together because they are pursuing the same anti-agalmic ends in different ways. More likely, though, the task of imagining a society without unfulfillable wants was simply beyond its creator’s abilities (no surprise there; it's beyond everybody else's).

The natural audience for this story is foggy-minded left-libertarians, but others can enjoy it, too, so long as they tune their incongruity detectors to a suitably low level.

July 24, 2002

Continuing with the Hugo Award short fiction nominees, here are my summary evaluations of the candidates for Best Novella:

1. “The Chief Designer” by Andy Duncan is fiction about science rather than science fiction and no worse for that. In a series of deft aperçus, it recounts the career of Sergei Korolev, the architect of the successful early years of the Soviet space program. Though he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his role in the Sputnik project, Korolev was mostly kept out of sight. To the extent that he was known at all to the outside world, he seemed like another faceless party functionary.

Told partly through Korolev’s eyes and partly through those of a fictional disciple, “The Chief Designer” describes a man whose existence in the former Soviet Union scarcely seems possible. The narrative begins in the Kolyma gold mines, the most dreaded isle in the Gulag Archipelago, from which Korolev was extracted at the beginning of World War II to work in the military rocket program. After the war, he used his position to push the USSR into a race to the Moon with the United States and his talents to make that race closer than should have been possible. (The Soviets’ loss of momentum after his premature death speaks for itself.)

Korolev emerges as an “internal emigré”, who dedicates himself to cultivating his own special garden despite the horrors that rule outside the Baikur Cosmodrome. His enclave seems detached from the rest of the world, a refuge for scientific endeavor. That detachment is the overarching theme of the story. By shutting out the Soviet world, the Chief Designer is able to live and work, but he always remains, as his widow bitterly exclaims in a final scene set three decades after his death, a prisoner, as unfree as the miserable zeks from whose ranks he was fortunate enough to be plucked. The services that he renders to the state are, like those of a prisoner, accepted as matters of course. (The story does not mention that he was forbidden to accept the Nobel Prize in his own name. Instead he delivered the thanks of “the Soviet people”.) In the end the state failed him in the most elementary of ways. Suffering from hemorrhoids, he was brought to Moscow for surgery and butchered by high-ranking, incompetent doctors.

As fascinating as the pictures of Korolev are the glimpses into the realities of the Soviet space program. Few readers will quickly forget the schoolboy pranks played on Yuri Gagarin on the night before the first manned space flight or the black comedy of the death plunge of Soyuz 1, whose pilot screams for help while Premier Kosygin reads him an inspirational speech on the steadfastness of Socialist Man.

Though the Chief Designer was our adversary, Americans have much reason to be grateful to him. It is unlikely that, without the pressure of the Cold War competition that he engineered, more or less against his masters’ will, our own country would ever have stepped very far beyond the confines of Earth.

2. “The Diamond Pit” by Jack Dann is neither science fiction nor fantasy but their ancestor, the tall tale. Central to the yarn is a mountain-sized diamond, discovered in Montana by a Virginia gentleman who turns it into both a hidden homestead and a source of unending wealth. Aerial barnstormer and narrator Paul Orsatti is shot down when he tries to overfly the area and imprisoned with other luckless aviators. He is not completely luckless, however - or so it seems - for he attracts the admiring attention of the proprietor’s beautiful daughter.

Driving the plot are two conflicts, the first between Paul’s infatuation with Phoebe Jefferson and his growing revulsion at the depravity of her surroundings, the second between Phoebe’s desire for Paul and her family’s determination that no guest may leave their domain alive. The two conflicts come together in a climax that reveals an unexpected traitor in the midst of the Jefferson clan.

Should I ever accumulate treasure beyond the dreams of avarice, I shall call on Jack Dann to design my manse. The Jefferson home is full of imaginative luxuries that are more fascinating than repetitious opulence. The dysfunctional family members are more ordinary: domineering father, sullenly defeated mother, demoralized son, whiney elder daughter and brilliant, spoiled, wilful Phoebe. The author wisely avoids making the characters as rococo as their environment, lest that be one strangeness too many.

Though the ending is morally satisfying, no one will call “The Diamond Pit” moving or profound. It is, on the other hand, exactly what a tall tale ought to be: entertaining and rife with astonishment.

3. “Fast Times at Fairmont High” by Vernor Vinge (printed in The Collected Stories of Vernor Vinge; available as a free download from Fictionwise until the end of August) is best described as contra-cyberpunk. The concepts are much the same: virtual reality, a pervasive Internet, ubiquitous computers, gigantic corporations, gaping economic divisions. But the scene painted with these colors is bright and optimistic, without more than a delicate touch of noir.

The setting is in a Internet age Hogwarts, where learning revolves around wearable computers and the World Wide Web. Juan, an insecure eighth grader who secretly uses drugs to enhance his academic performance, undertakes a school project in partnership with an overbearing Chinese girl whom he barely knows, chaperoned by her half-crazy grandfather. In the background is Juan’s manipulative “best friend” Bertie, whom the girl loathes but whose perhaps tainted assistance she reluctantly accepts. The kids stumble on what may be either a sinister coverup of scientific malpractice or a movie preview. Whichever it is - and we are left in uncertainty - no corporate goons attack the intruders. The only obstacles that they face derive from nature and their own awkwardness at working together.

The author’s apparent intention was to transpose a familiar high school story to a vastly different environment, just as J. K. Rowling has interjected magic into the British school story genre. He doesn’t quite succeed. Were magic possible, I can believe that it would be taught at institutions like Hogwarts. Fairmont Junior High, by contrast, fails to compel suspension of disbelief. If it represents the future of learning, our descendants are in trouble, for, so far as the reader can tell, the course of study consists primarily of lessons in how to pose questions to a kind of super-Google.

The interaction of the characters shows promise. In the beginning, Juan is unhealthily dependent on Bertie’s help and approval. By story’s end, he has developed a modicum of self-sufficiency. This maturation does not, however, spring from the difficulties that he and his partner Miriam confront and overcome. In fact, they don’t do much confronting and overcoming. They blunder around with their era’s version of obsolescent technology and finish their project successfully thanks to gear furnished by Bertie for his own cloudy purposes. Juan’s change of character comes from none of that but when Miriam’s grandfather assures him that there’s nothing wrong with performance-boosting chemicals; he should be glad to have them, while taking care, of course, not to get caught. Thus he becomes a contented, well-adjusted cheat. Not a message that anyone but a hardcore Bill Clinton fan is likely to appreciate.

The author says that he plans to work the materials in this story up into a novel. Having great confidence in Vinge novels, I imagine that a more expansive version will fit the many good ideas of the novella into a better-realized future and a better-rounded story.

|

|

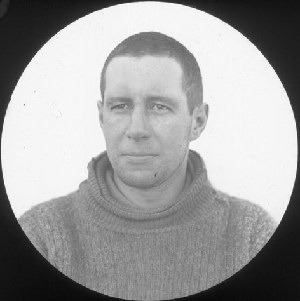

Captain Lawrence Edward Grace Oates, 1880-1912

|

4. “May Be Some Time” by Brenda Clough, the first installment of a novel (part 2 appears in the July/August 2002 issue of Analog), brings a real figure from the not-too-distant past into our not-too-distant future. Captain “Titus” Oates died on the Scott Antarctic expedition in 1912. Unable to keep up with his companions, he hoped to improve their chances of survival by leaving them. As he crawled into a blizzard, his last words were, “I am just going outside, and may be some time.” His body was never found.

In this story, he is rescued by a time travel expedition and taken to America 40 years hence, where his health is restored by clonal surgery. He then faces a task as difficult in its own way as trekking through the ice, namely, finding a place for himself in a thoroughly alien era.

As many observers have noted, the Great War opened a gulf in Western civilization. Attitudes that were, for good or ill, commonplace before then now seem strange. It is easy to loath the unexamined racism, prudery and militarism of our ancestors - and hard not to admire their courage, honesty and devotion to duty. The fictional possibilities of this cultural contrast are shown brilliantly in Connie Willis’ To Say Nothing of the Dog, where moderns are plunked down in the Victorian Era.

Brenda Clough takes her time traveler in the opposite direction and is serious rather than comic. Unfortunately, she portrays Titus as such a stiff-upper-lip stereotype that neither his reactions to the future nor the future’s to him are as interesting as they ought to be. Worse, the upper lip trembles at unlikely moments. A man who fought in the Boer War and trekked to the South Pole breaks down at an IMAX theater! On other occasions he is remarkably chuckle-headed, for instance asking the British ambassador whether George V is still King.

The scientists who interact with Titus are a dull lot: earnest, politically correct and thoroughly ignorant of history. Titus, despite his eagerness to grasp the fundamentals of his new world, finds them too boring to attend to closely, and the reader will probably agree.

At the risk of arrant presumption, I recommend that the author delete from her hard drive all that she has written so far, take a couple of months off to read everything by Rudyard Kipling and G. A. Henty that she can find, with a leavening of Anthony Trollope and Jerome K. Jerome, and then return fresh to Captain Oates. She has a really nifty idea here. It would be a shame for it to be executed less than wonderfully.

5. "Stealing Alabama" by Allen Steele describes the heisting of mankind's first starship by a vast conspiracy directed against a future American tyranny. The dictatorship is labeled "right-wing", but, except for a penchant for naming things after 20th century conservative politicians (mostly Southerners), it is just your generic police state and not an outstandingly oppressive or efficient one at that. Its inability to get an inkling, until the very last minute, of a plot involving a hundred or so people, many of them less than scrupulous about security, suggests that the United Republic of America will be undergoing a regime change long, long before the Alabama reaches Tau Ceti.

Smooth narration glides over numerous absurdities. What motive does the URS have for undertaking the fantastic expense of planting a colony with which it will have no contact for at least 242 years? What motive does the opposition have for exiling a large number of its most capable supporters? Why doesn't an opposition that can manipulate the government apparatus so expertly devote its efforts to a coup d'etat?

As the operation proceeds, the good guys commit blunder after blunder but are saved by the superior stupidity of their adversaries, plus a little arbitrary help from the author. Inconsistencies abound. Some of the DI's ("dissident intellectuals") tapped to participate in the plot know nothing about it; others, with equally little need to know, have beans to spill to the secret police. One of the main characters wavers between knowledge and ignorance: He doesn't know why he is being arrested but does know to take along an item that is vital to the hijacking's success. The worst Mission Impossible script was more plausible than this mishmash.

If one nonetheless beats one's disbelief into submission, the story does not lack virtues. The writing is fluid, the lightly sketched political situation moderately believable and the characterization fairly strong. Particularly good is the portrayal of a frightened dissident family as its mood swings from despair to hope to fear that their hope will be snatched away by father's moment of carelessness. These characters and this excellent writing deserve a better plot.

July 20, 2002

Hugo Award balloting closes on the 31st, so it is too late for my opinions to influence very many other voters (not that they would anyway). Still, having actually read every fiction nominee this year, I may as well distill that effort into a few comments on their merits. Earlier, I offered betting odds on the novels. Voting in the shorter categories has been too unpredictable in the past to make handicapping possible, so I'll simply present my personal preferences. We begin today with the Short Stories. Except for Ursula K. Le Guin's "The Bones of the Earth", all are available on-line.

1. “The Dog Said Bow-Wow” by Michael Swanwick is the first of the author’s “Darger and Surplus” series, tales of roguery set in the distant age after mankind has expelled the demons of the Internet. Cybernetics is superseded by autistic idiots savants and hideously transformed human computational devices, one of which now reigns over England as Queen Gloriana the First. Two new-met thieves - one of them a dog bioengineered into quasi-human form, the other a fake savant - insinuate themselves into Buckingham Labyrinth, the maze engulfing the ancient palace, in a scheme aimed at making off with a priceless jeweled necklace. After an abundance of bizarre twists and turns, they approach their goal, only to find that they have overlooked one vital detail.

The setting for this romp has qualities of verisimilitude that are rare in serious stories, much less in comedy. A high-tech future centered around biology rather than electronics might well look like this and be peopled creatured by adventurers (“something more than mischievous but less than a cut-throat”) like Aubrey Darger and the caninoid Sir Blackthorpe Ravenscairn de Plus Precieux (“‘Call me Sir Plus,’ he said with a self-denigrating smile, and ‘Surplus’ he was ever after”).There is nothing deep about the pair’s exploits, but they are rousing entertainment.

2. “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” by Mike Resnick (also available from Fictionwise as a free download until the end of August) presents its protagonist with an acute, impossible-to-resolve moral dilemma. Genetic engineering has produced an ideal source of animal protein for billions of malnourished children, but, as reporter McNair (“I used to have a first name, but I dumped it”) learns during the first-ever tour of one of the huge ranches where “Butterballs” are raised, the new creature’s genotype includes an unplanned-for and unsettling ability.

McNair discovers MacDonald’s secret gradually, and the data remain ambiguous. Refreshingly, there is no corporate villain. The company’s motives are pure to the point of Pollyannism, the PR flack who guides the tour develops into a sympathetic character, and no thugs leap out from the bushes to keep the hero from finding out too much. It isn’t often that a writer acknowledges that irreconcilable conflict can exist between two goods, as well as between good and evil.

The reader, like the reporter, doesn’t know in the end whether revulsion at eating Butterballs is sheer sentimentalism or the only morally possible reaction. That dilemma can stand for many that we potentially face as the concept of designing life forms moves from “The Island of Dr. Moreau” to laboratory. McNair finds no solution, and the personal course of action that he chooses contradicts his public stance. He is not happy to find himself in that position. In years to come, many of the rest of us may have occasion to join him in discomfort.

3. “Spaceships” by Michael A. Burstein takes place in an era when trillions of humans live as disembodied energy entities. Its hero is a loner, who eons ago withdrew from contact with others and now inhabits a sphere a light year in diameter, populated by his immaterial form, a binary star system and his collection of spaceships. As the story begins, he receives his first visitor, a tourist come to look at the ships. Naturally, the new arrival’s purposes are not so simple and benign as they initially appear.

This lyrical and tragic tale asks why it is important to preserve knowledge of the past. The author takes sides with the traditionalist Kel but does not pummel readers with preaching. The vision of antique relics, useless except as connections with the ancient roots of humanity, is left to make the argument on its own.

The major weakness in the plot is the incomprehensibility of the visitor’s motives, or, rather, of the motives of the backstage villains who have put her up to her skulduggery. The stated reason for their desire to see the ships destroyed - that they are more useful as energy than as matter - makes no sense; they raise no objection to Kel’s retention of two stars. Irrational hatred of the past is an arbitrary explanation - mere motiveless malignity - and leaves the debate too one-sided to be satisfying. Perhaps the whole exercise is simply a bizarre initiation ritual, which reduces the story to an anecdote about a destructive frat prank.

4. “The Ghost Pit” by Stephen Baxter presents far future hunters in pursuit of enigmatic prey. The quarry are “Silver Ghosts”, beings that can manipulate space-time but have been driven to the verge of extinction by the relentless expansion of humanity. When what may be the last “ghost pit” is discovered, an antagonistic team, yoking a boastful veteran to a first-timer inspired and burdened by memories of her famous mother, takes a spaceship into it. The place proves to be much stranger than they had anticipated as well as more dangerous.

As one expects from Stephen Baxter, hyper-scientific marvels flower effortlessly and plausibly. The human side is far weaker. Why did such a mutually distrustful pair as L’Esh and Raida enter into partnership, and why does Raida, at the end of the story, renew their pact? L’Esh has done nothing in the interim but mislead, insult and try to murder her. Nonetheless, she saves his life, though she has earlier been plotting to kill him and has no discernible reason to change her mind, and, as the scene fades, is negotiating terms of another joint hunt.

Overlaying the plot is a thick layer of moralizing about mankind’s destruction of other species, and the ending suggests that this anti-ecological impulse will now find a new outlet as the Ghosts fade away. So what we have is a story about two nasty people doing nasty things and surviving to do them again. If they had discovered trust or affection or the importance of shared humanity, their survival would, or at least could, bring the series of incidents to a satisfactory end. As matters stand, the sense of wonder evoked by the gigantic structure of the ghost pit and its contrast with the war ravaged bone pile within make this work memorable, but I suspect that I will prefer remembering to reading it again.

5. In Ursula K. LeGuin’s classic novel A Wizard of Earthsea, the hero’s first teacher is introduced as “Ogion the Silent, who tamed the earthquake”. “The Bones of the Earth” (published in Tales from Earthsea; not available on-line) tells how the earthquake taming really took place and sketches the life and character of Ogion’s teacher Dulse. The tone is heavily - some will say cloyingly - elegiac, as the elderly wizard, half lost in memories, embarks on a final task that necessitates the use of an irreversible transformation spell learned many decades ago from his own aberrant teacher. Also present is a touch of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

Taken by itself, the story is full of well-turned lines but is more a vignette than a tale. Dulse faces no challenges in sensing the impending tragedy, knowing what to do about it and acting on his knowledge.

As an addition to the Earthsea canon, this piece continues, in a minor way, the author’s project of retuning her subcreation to the exigencies of contemporary feminism. In the original trilogy, sorcery was open by its nature only to men. Now that embarrassing remnant of patriarchal thinking has to be patched up and explained away. Here we learn that Dulse was taught his craft by a female, which is fitting for this particular story but erodes the imaginary reality of the mythos.

Overall, “The Bones of the Earth” is a fine series of scenes and images that lack the conflict essential to story telling. If they could instead be rendered as a painting, the finished artifact would be beautiful.

July 8, 2002

The overhanging presence at Westercon (Los Angeles, July 4-7) this year was an absence. Bruce Pelz, the convention chairman and a leading personality in Southern California fandom for four decades, died only a few weeks ago, less than an hour after submitting his chairman’s letter to the program book editor. The memorial in his honor, appended to a Fourth of July meeting of the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society, was one of the convention’s best attended events. There were, if I counted correctly, 35 eulogies, and a couple of hundred fans remained for three hours to listen to all of them (even after the hotel shut off the air conditioning for the night). The freshest, to my mind, were reminiscences by Bruce’s daughter (from his short-lived first marriage - after separating, he and his ex threw a “divorce party”, with a cake topped by a bride and groom turned back-to-back), who talked about her father’s taste in toys, children’s books and travel.

The range of Bruce’s interests and activities was more astonishing than I had realized. One doesn’t expect a single human being to publish over a thousand fanzines and go on dozens of cruises (42 since 1989, according to his widow Elayne) and run the hospitality suite year after year at the annual convention of the Special Libraries Association.

Shortly before he died, Bruce proposed a new level of LASFS membership. “Pillar of LASFS” was to be the next step beyond “Patron Saint”, requiring a $4,000 lump sum donation. It looks like Bruce himself will become the first pillar. By the close of the con, two auctions plus miscellaneous gifts had raised over $3,300 toward that goal. (My contribution was to bid $100 to not have a book of poems by Leonard Nimoy included in the auction.)

Shorter and sadder than Bruce’s was the Friday night memorial for George Alec Effinger. Harlan Ellison delivered the eulogy, which was full of affection for “Piglet” but was perhaps excessively candid about his tendency toward self-destructive behavior. Harlan’s summary was, “He just wouldn’t get out of his own way.” That is undoubtedly true, but it isn’t the whole truth. Notwithstanding his multiple problems, George wrote and published over 15 novels, most of them first rate, and a worthy body of short fiction. Plenty of healthy, well-adjusted writers have done worse in both quantity and quality. There is something remarkable, if not heroic, about the ability to write ably under the handicaps of debilitating disease and persistent addictions.

But this is not the proper cheerful note on which to get a con report under weigh. Let’s go back to the beginning.

Conagerie, the 55th Westercon, was held at the Los Angeles Airport Radisson, an adequate though slightly dreary venue. The facility’s best point was the penthouse, a circular structure with floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking LAX, where the con suite was located. The worse was the elevators, which faltered by Thursday afternoon. On Sunday, a frustrated attendee posted a “suicide note” next to the main floor buttons, proclaiming that he could wait no longer for a car with room to breathe. The predominant hotel color was brown, which synergized with inadequate lighting to generate feelings of impenetrable gloom.

Attendance was below most expectations, only two-thirds the number that normally shows up at Loscon. Westercons have suffered a run of poor numbers lately, but those drew no comments when the con was in El Paso or Honolulu or Spokane. Fewer than a thousand warm bodies in L.A. made worry about the future of Westercon a major conversational theme.

Transient factors explain a great deal. There apparently wasn’t much advance local publicity, the airport shooting on the Fourth of July may have discouraged some locals from coming, and the imminence of a Worldcon in the vicinity may have made a mere Westercon less attractive. My own theory is that a larger process is at work and that Westercon is volens nolens evolving into the West Coast convention for traveling fen, the niche that Norwescon might have occupied if it had not veered into countercultural parochialism in the late 1980’s.

While the crowd may have been relatively small, it was geographically well-rounded (I would have said "diverse", but I'm trying to eliminate that word from my vocabulary) and included a high proportion of well known figures. For instance, over a dozen past, present or future Worldcon chairmen were on hand, the most that I’ve seen anywhere other than Midwestcon, SMOFcon and the Worldcon itself..

The program was planned in anticipation of a more populous gathering: five or six tracks from noon Thursday through late afternoon Sunday, plus films and round-the-clock filking. In a variation on the schedule introduced at Chicon 2000 and since adopted by a number of regional conventions, slots were 75 minutes and moderators were given the discretion to call a halt at any point after about 55. Thus active panels ran almost till the next item’s starting time, while those that were flagging could be tactfully cut off. This system impressed me as a good compromise between the formerly standard 60 minute slots, which force too many panels to close in a flurry, and Chicon’s 90 minutes, which is probably a bit too long for the average discussion.

Having no duties, tables or parties to attend to, I saw more than my usual scant share of programming. Of especial interest were interviews with GoH Harry Turtledove and with Connie Willis (not a GoH but always worth getting up on stage). The interviewers, Lynn Maners for Turtledove and Steven Boyett for Willis, were unusually well prepared, and the interviewees were both in good form. Harry’s fans will be happy to know that Ruled Britannia, a stand-alone set just after the conquest of England by the Spanish Armada, will come out in November. It pits subversive playwright Will Shakespeare against royal agent Lope de Vega. H. N. Turteltaub, his historical novelist persona, also remains active, having just turned in the manuscript of a novel set a year after Over the Wine Dark Sea.

Connie lamented the increasing difficulty of writing comedy in a world that is passing beyond self-parody. “The other day I read an article in Esquire about restaurants in New York that don’t stop at a wine sommelier. They also have sommeliers for water. What’s the point of making up something absurd when it is topped by Esquire?” Nonetheless, she promises to keep trying. Her next novel will continue the series begun with Doomsday Book and To Say Nothing of the Dog, maintaining the humorous vein of the latter. The action will be set during the Blitz, with side excursions to Dunkirk and elsewhere. At one point, she opined that every comedy should include at least one unbearably painful scene, which is why she sees no contradiction between screwball humor and the darkest hour of a world war.

Among the other panels that I attended, the most interesting observation came from the audience during the panel on “Current Fanzines”, when someone noted that the Internet has greatly reduced the number of feuds carried on in the zines. Feuding on-line is so much quicker and easier that the old medium is no longer optimal for that purpose.

The most reassuring panel was “The Year in Astronomy and Astrophysics”, during which Mark Olson assured us that predictions of giant tsunamis within the next century are balderdash, being based on models that are not supported by experience. If they were accurate, similar events would already have occurred and would have left behind unmistakable evidence.

The Art Show was of moderate size and high quality. I saw nothing amateurish and several large pieces that I would gladly have purchased if only unlimited funds and luggage space were available. As it was, I snapped up a bunch of small prints by James and Cathy Wappel, who were the best represented artists in the auction. An oddity was the sparse representation of jewelry and sculpture, which have become a progressively larger part of most SF art shows during the past several years. Here the trend was abruptly reversed; no more than maybe ten percent of the entries fell into those categories.

Sandy Cohen and Tadao Tomomatsu deserve kudos for conducting an art auction that was entertaining without dragging to excessive length. About 45 pieces went for $3,532 in less than 90 minutes, including a ten-minute intermission.

Parties were sufficiently numerous and lively, easing fears that an aging fandom is starting to fall asleep at dusk. Kansas City in ‘06 at last made a serious appearance, with two nights of bland but adequate partying. The bid still lacks a theme and real excitement. The pleasant young woman serving punch, when asked why one should support K.C. over L.A., offered only that 2006 would be the 30th anniversary of the last Kansas City Worldcon. She did not go on to try to evoke MidAmericon nostalgia. I wondered whether she knew anything about that renowned convention, which she was obviously too young to have attended.

L.A. in ‘06 introduced the “Space Cadets Aptitude Test”, in which I qualified as a Microgravity Facilitator. Their party was extremely crowded on Friday night. It was not empty on Saturday, but one could find breathing room and conduct conversations without shouting.

UK in ‘05 and Nippon in ‘07 combined their efforts into a party notable for single malt Scotch and plum wine, which I trust not too many people tried to drink in tandem.

In fannish gossip, many heads were shaking over ConJosé’s low membership numbers. Unless there is an upsurge at the door (not at all impossible in California), this will be the smallest U.S. Worldcon since San Antonio. The economy was the most frequent explanation, but mediocre marketing hasn’t helped. On the positive side, the once-conspicuous intracommittee tensions are either resolved or better hidden. More work than usual will have to be done at the last minute, but the concomm is certainly capable of rising to the occasion.

The newest bid rumor is Columbus in ‘07, to be sponsored by the group that runs Marcon. Columbus was never able to win a Worldcon back when it was a fannish powerhouse, and its eminence is now much eroded. Marcon has a reputation as a “media con”, which is probably unfair if one judges by the committee’s intentions rather than the event’s actual audience. (It was a long-time Marcon attendee who looked at a set of Chicago in 2000 trading cards and professed herself unable to recognize the name of a single author in a group that included Poul Anderson, Gordon R. Dickson, Jack Williamson, L. Sprague deCamp, Connie Willis, Mike Resnick et al.) If the bid gets off the ground, its hopes will rest on the possible unwillingness of American fans to vote for an ultra-expensive Worldcon in Japan. More likely, we’re seeing a stalking horse for a NASFiC bid. If SMOF-favored Nippon should by some happenstance lose, I predict a sudden upwelling of support for reinstating the zone rotation system.

The inexplicable hole among Worldcon hopefuls is 2008. Erik Olsen told me that he had tried to persuade the organizers of the prospective Chicago in 2010 bid to shoot for ‘08 but was ignored. He points out that 2010 is a natural year for an Australian bid, which would be aided if the voting were in Japan. The Aussies are unlikely to aim at ‘08 or ‘09, as two trans-Pacific Worldcons in three years is more than fandom can be expected to embrace.

With Glasgow unopposed for the 2005 Worldcon, it looks like there will be a contest between Seattle and Charlotte for the NASFiC. Seattle held an exploratory party at Westercon and is set to launch at ConJosé. Charlotte has been silent since Irv Koch stepped down from leading the bidcomm, but everyone assumes that it will go forward.

Arizona won the 2004 Westercon with only hoax opposition. For 2005 the race will pit San José (mostly the group that puts on Baycon) against a Calgary bid led by John and Linda Mansfield. San Diego has announced for ‘06 and is likely to encounter no serious opposition.